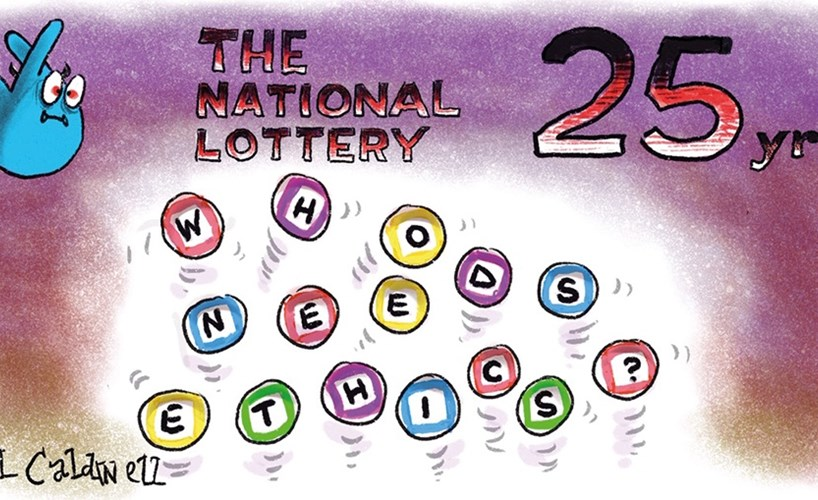

Ethical objections greeted its arrival 25 years ago. How things have changed since then, writes Ted Harrison in The Church Times.

Last Tuesday, it was exactly 25 years since the first National Lottery draw took place. An audience of 25 million, most of them hopeful punters, watched a man from Camelot set the balls rolling. That night, seven lucky viewers became instant millionaires.

At the time, many church leaders expressed disapproval. The Government should not encourage gambling, they argued; it would be the less well-off who would waste their money chasing hopeless dreams at extravagant odds.

Today, however, the Lottery has become so much a part of everyday British life, and churches receive so much in funding from the proceeds, that the awkward ethical questions have been quietly forgotten.

It is undeniable that good causes have benefited significantly from the Lottery. From every £100 spent on lottery tickets, £24 goes to good causes. It is not only charities that benefit: many medal-winning elite athletes are funded by the lottery, as are visual artists and musicians. Seventy per cent of the cost of raising Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North, for example, came from lottery money, and the Eden Project in Cornwall was funded to the tune of £37.5 million from the same source.

It could be argued, however, that these, and the hundreds of smaller projects which receive money from the lottery, should be paid for by the Government through taxation. In that way, everyone who benefits would be contributing, with the richest in society paying the most. As it is, the burden falls disproportionately on the less well-off — for it is they who are more likely to play lottery games.

Ten years ago, a survey by Theos confirmed the suspicion that lottery players do, indeed, come from poorer backgrounds. The lower-paid and unemployed spend significantly more on lottery tickets and scratch cards, as a proportion of their household income, than more affluent players.

This was confirmed by previous studies, such as a 1998 study by Warwick University, which suggested that those who had left school and not gone on to further or higher education were more likely to play, and lottery takings in the UK rose bout eight per cent in the five years after the financial crisis in 2008 as austerity kicked in and people had less to spend. There is, perhaps, some truth in the description of the lottery as a voluntary tax on the poor.

While lottery money undoubtedly goes to fund organisations and causes that address social problems and inequalities, I suspect that heritage lottery funding tends to favour projects that are mostly of interest to those who do not play the lottery.

I never buy a lottery ticket, and I strongly suspect that very few of the people I see regularly in church do either. Yet, earlier this year, the historic mosaic floor in my parish church was repaired thanks to a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. I am delighted that it has been restored to its original high-Victorian splendour, but I am aware that there are hundreds of local people in my town who do play the lottery every week and who will seldom, if ever, go into the church.

Since 1994, the National Lottery has raised more than £39 billion for good causes, of which £8 billion has gone to heritage projects. In May, it was announced that four cathedrals — Leicester, Lichfield, Newcastle, and Worcester — would be benefiting from more than £8 million of lottery money (News, 17 May). It is now considered entirely acceptable for the Church to take the proceeds of gambling to further its work.

Five years after the lottery began, the Methodist Conference reversed its original opposition to the lottery when it agreed that Methodist projects and causes would be permitted to make applications for lottery money. The Methodist Church continued to voice concerns that the lottery normalised gambling, but concluded that there was no evidence, as yet, that the lottery had contributed to problem gambling in society.

The lottery does not, however, consist simply of the regular national draws: it also makes money from the millions of scratch cards sold under the National Lottery brand. Scratchcard addiction is now a recognised problem. A tabloid newspaper story, three years ago, recounted how a man from north Wales had lost £60,000 in just six months. Using his life savings, he would buy £200 worth of cards at a time, lured by the remote hope of winning £250,000.

DraggedImage.6ad28476ee2343b3af219c03e0c8aca5.png